In one of Shakespeare’s most quoted lines, the Scottish witches in the play “MacBeth” cook up a magic potion with the words “Double, double, toil and trouble/Fire burn and cauldron bubble.” In North America, we have witches that produce a potion without chanting. The witch-hazel tree is a legitimate medicinal plant, and special in several ways. Hamamelis virginiana is the species common in the eastern forest, Hamamelis vernalis is common in the southern US, and the Asian Hamamelis mollis and H. japonicus can be found as ornamentals introduced for gardens and urban landscaping.

Extracting fluids from the leaves or bark of the witch-hazel tree provides a tea or ointment. Among the many compounds captured this way is tannic acid, a common plant chemical that was used in the old days in making leather (hence the reference to tanning). Tannins have some antibiotic properties, and along with the other components they give witch-hazel extract an astringent property, meaning that they help tighten the skin and close down blood circulation locally. This was useful in pre-industrial days to reduce inflammation, reduce infection, and stop bleeding. Witch-hazel is still used today as an effective treatment for acne, or to soothe a sore throat.

Long a folk remedy, witch-hazel extracts have been used to treat skin ailments of various sorts, including “insect bites, stings, teething, hemorrhoids, itching, irritations, and minor pain,” according to WebMD. However, witch-hazel has some dubious credits to its name, such as that dowsing rods used to find water underground were to be made of witch-hazel branches. Just because some folk knowledge is valid does not mean all of it is!

Witch-hazel blooms in late autumn, and through winter, even in January. This means it might be the last to bloom and the first to bloom on the calendar of events that a nature-watcher records. The flowers are simple, mostly just the flattened stamens of the male parts, with no petals or other evident structures. With few bees around in late autumn and winter, witch-hazels are likely pollinated by beetles that come to eat the delicate floral parts, by winter moths, or by the ever-present flies that will find the showy blossoms in the naked understory.

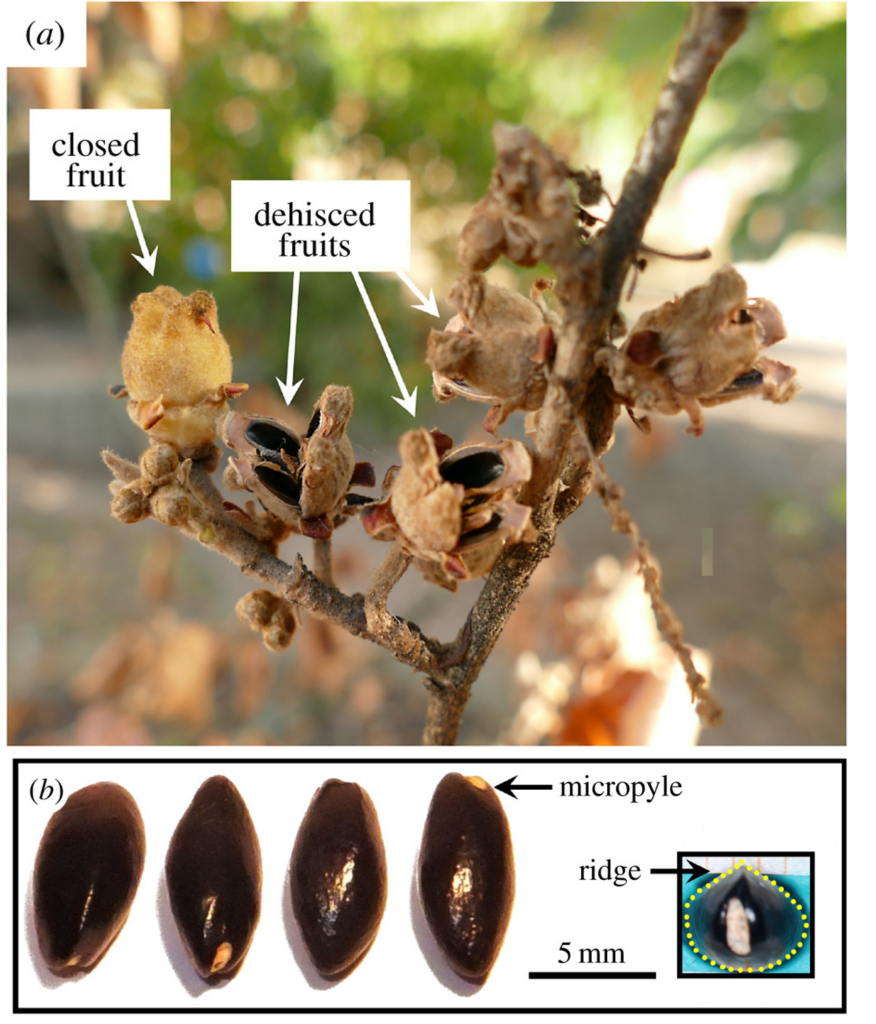

Witch-hazel flowers pollinated in winter do not mature until late summer. By then, the capsule that protects them is dry. In drying out, the capsule’s outer walls shrink more than the interior, and substantial forces balance around the circumference until there is a catastrophic failure, and the capsule explodes. Perhaps readers have witnessed a similar effect with ripe jewelweed pods (“touch-me-not”) that burst when touched and throw seeds. This is called ballistochory, which means “ballistic seed dispersal,” (or, like a bullet.) The sudden release of force throws seeds far away, at a speed of more than 25 miles per hour, with an initial acceleration of about 2000 times that of gravity! The seeds themselves are shaped like little footballs and will spin as fast as 400 rotations per second, going straighter and further than a tumbling seed. This Halloween Witch has unusual powers!