We all think we are good shoppers even though we have different goals. Imagine, in grocery store full of choices, that some shoppers will always buy the familiar product they already know and like, others look for the least expensive, others choose the “healthiest” product, while still others may choose based on getting in and out of the grocery in store the least amount of time. Favoring different products, each person may have made the best choice according to his or her goals. That is why we have an entire aisle of toilet paper: one-ply, two-ply, quilted, scented, single roll, four-pack, twelve-pack, septic-tank-friendly, etc. But, there is a principal of animal behavior and psychology that shows that in certain contexts we make irrational decisions that we would disavow if we were conscious of it.

When we choose between alternatives, we must balance cost and reward. The problem with the grocery store survey is that individual shoppers may evaluate cost and reward quite differently. Someone who takes a city bus to the store values space in her bag to carry food home. Buying the twelve-pack of toilet paper would mean she can’t carry much in the way of food, which is a substantial negative to her. The two single rolls will leave more space in her bag for milk, bread, and eggs. Even if it is a little more costly per roll in dollars to buy single rolls, it is a lot less costly in carrying space. In contrast, the suburban mom with an SUV doesn’t care how big the package is if she saves money by buying in bulk. So far so good, but it turns out that underlying all these decisions is an ancient, irrational drive that is found in humans and animals regarding balancing costs and rewards. We can see it in certain simple circumstances.

Imagine that you are in a bicycle shop, looking for a bike to ride around your neighborhood and maybe to the park, casually. There are two styles of bikes for sale: a solid, no-frills, bike for $200; and a somewhat better, brand name bike with pretty paint for $450. Many people will choose the $200 bike because they feel that the extra cost of $250 dollars (more than double!) seems to be too much to get somewhat better construction and nice paint when the $200 bike will do the job just fine. However, if there is a third style, a beautiful, sleek, hand-crafted bike for $1,900, many of the customers who would have taken the no frills bike for $200 will now decide to step up to the brand name $450 bike. The $450 bike is expensive compared to $200, but it looks pretty good compared to $1,900. This is irrational because the brand name bike was too expensive when we saw the $200 alternative, and that doesn’t change when we suddenly see an even worse choice. Yet, we make this irrational choice because we recalibrate our scales regarding cost and reward depending on choices we see. It is as if we start by measuring how far apart the extremes are, and so with a deeper list of “bad” choices, we are more generous about what is a “good” choice. This may be the real reason showrooms have one super luxury sports car on the floor: not to sell the sports car, but to sell more of the other, not-as-expensive, luxury cars.

This general behavior has been demonstrated in other contexts, such as how university students buy beer in a bar. If you have two kinds of beer, one for $1 a glass and one for $3, you find that students will mostly buy the $1 beer. If you also offer a premium beer at $6, you will sell a lot more $3 beers. This will work pretty much anywhere.

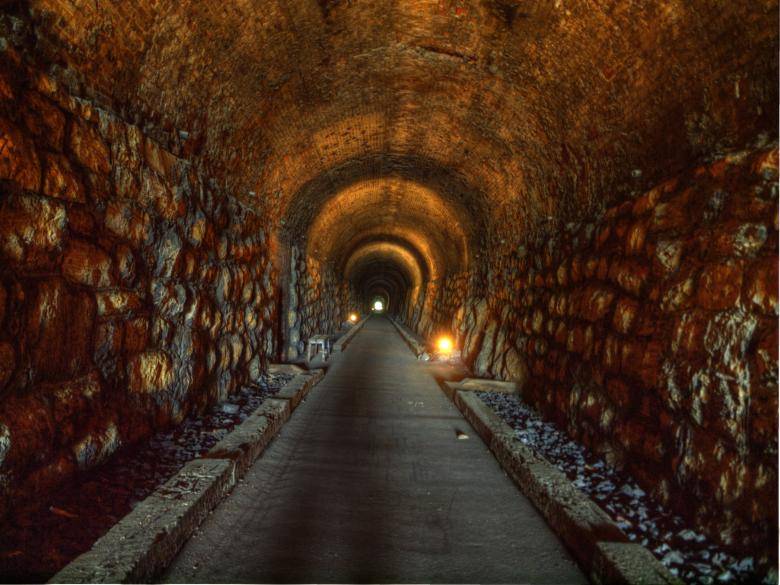

This logical fault has also been demonstrated in intelligent birds, the Gray Jay, by presenting them with different numbers of nuts (rewards) earned at different costs: walking down a tunnel, (which they do not like to do) that is long or short. If they can go down a short tunnel for three acorns, they will not go down a long tunnel for four acorns. But they will choose the long tunnel if they have a third choice, a very long tunnel with four acorns. They favor what was a bad decision when they see one that is much worse. Studies show that animals as distant as ants will make similar errors. This may be a very deep and general bias in the way animal cognition works to balance costs and benefits.

So, were you a rational shopper this holiday season? They got me on a windshield ice scraper.