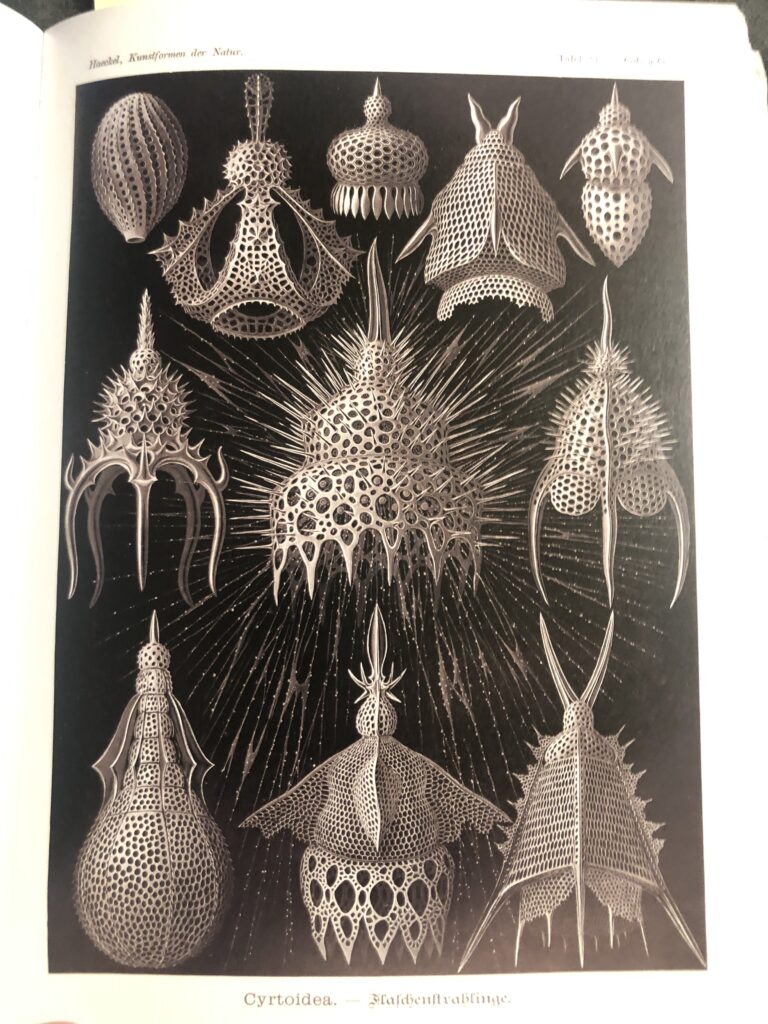

Scientists often represent natural phenomena through technical illustrations. While these are intended as explanations, they are often appreciated as art. Humans apparently enjoy witnessing beauty in the world around them. This is easily recognized in paintings of landscapes or portraits of birds in the wild. But are technical illustrations of jellyfish and plankton really art? Definitely, yes.

Whether a given presentation is art or not has been an enduring controversy. Critics may argue that photography by itself is not art. They may state that some intentionality on the part of the photographer is necessary to convert photographic documentation into art. Does the photographer intend that we appreciate the way the light glistens off the leaves, and how the dark shadows beneath the trees in the foreground contrast with the sunlit fields beyond? That is what a painter creates purposefully, and the photographer must capture his subject intending to show us this precise “beauty,” or we do not call it art. How should we regard scientific illustration that intends to present a literal documentation of form? Can that be art?

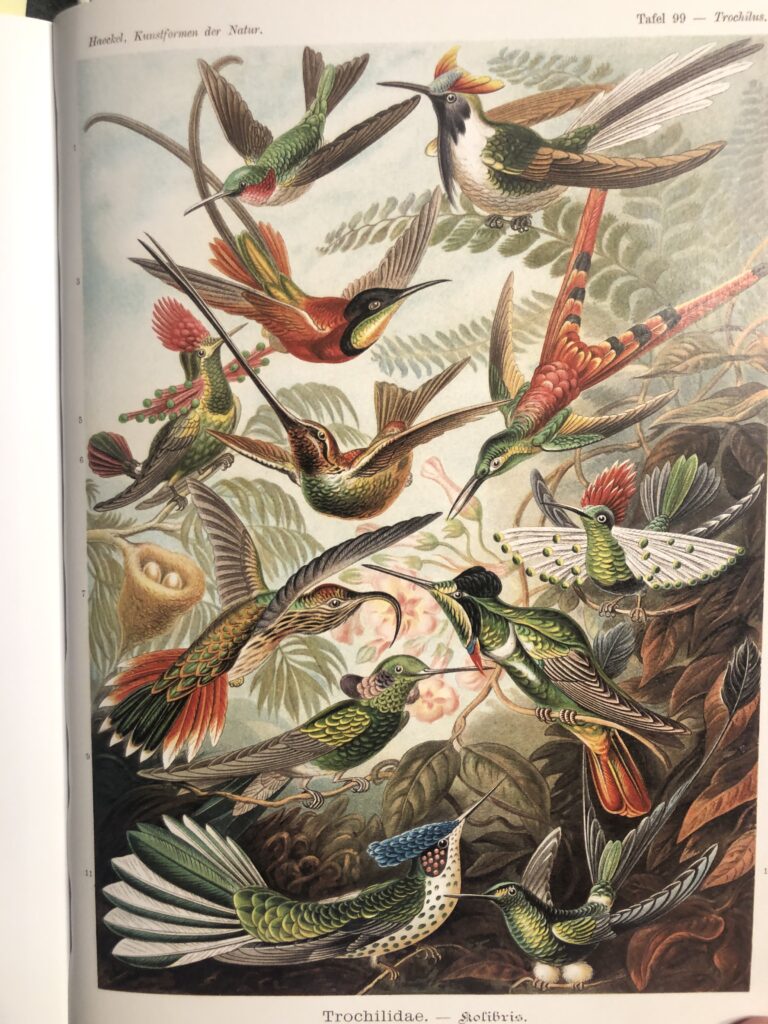

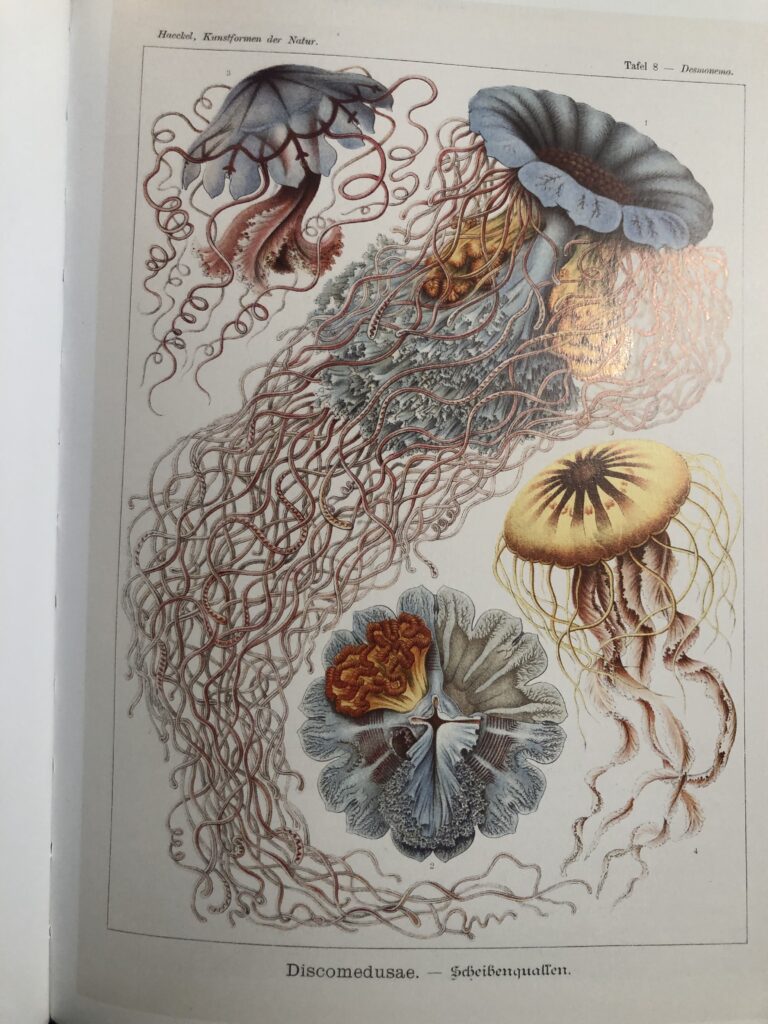

In hundreds of detailed drawings on many kinds of animals and some plants, Ernst Haeckel documented precise form, anatomy, and sometimes color. Haeckel was trained as a physician, but is better remembered as the most famous and respected biologist of the late 1800s. He was among the most important early adherents to Darwin’s perspective on evolution and principles of natural selection. Twenty-five years younger than Charles Darwin, Haeckel may well have out-ranked Darwin in some people’s minds by 1900. He was also a spectacular artist, presenting the specimen in such a way as to accentuate certain aspects of beauty, symmetry, and detail. Haeckel published several treatments of various animals, culminating in 100 plates of illustrations, in ten installments of ten plates each, from 1899-1904. The title of this work was Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms in Nature) which certainly indicates purpose.

Today, with powerful tools such as electron microscopes or laser imaging, we can document life forms better than ever before. We can recreate structures with 3D printers, or design Virtual Reality models for study without any physical product at all. Yet, there will always be something very compelling about the beautiful hand-drawn scientific illustrations of Ernst Haeckel.

All images from The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel, 2021.

Taschen GmbH. ISBN 978-3-8365-8428-9