Whether you call them lightning bugs or fireflies, you are probably pleased to see them on a warm summer evening. They are fascinating in several ways, and this blog will focus on the origin and elaboration of the light displays that we all enjoy.

Many insects can generate light, and fireflies (beetles in the family Lampyridae,) are only one lineage among them. Because they use light in courtship, they are very evident to us. But the lights we see flashing in the trees or over a field at night did not originate to fill that function. The organ that produces light first appears evolutionarily in the larva, the wingless grub-like form that is the immature. Generally, they can be found near the water’s edge at a stream or pond where they are hunting snails and worms at night. They may glow faintly or strongly from the underside of their abdomen. And why would they do this? Fireflies are toxic, producing the same class of poison as found on a toad’s skin, and taste terrible (yes, I have tasted them!) Toxic, venomous, and distasteful insects usually advertise themselves as being dangerous by having highly contrasting colors and stripes so that a would-be predator will learn quickly to stay away. Such warning coloration would not be visible in the darkness of night, but a glowing light is an effective advertisement. Many species are still limited in that only the immatures generate light, and adults do not.

Someplace in their evolutionary history, the development of the beetles changed such that the light organ was retained through metamorphosis and was functional in adults. Initially, adults used the light just as the larva does, as a warning that it tastes terrible. Some species may have a dim, constant glow, while others glow in distress, as a warning, such as when a predator takes hold of it. To find mates, these fireflies still use the ancestral system of sex pheromones rather than the glow of the light organ.

For some lineages the light took on a form of communication beyond the warning. A male searching for a female might use the glow of her light, or he might flash a particular signal to which she replies. For her part, the female may be watching a number of displaying males and choosing among them as other species do with male displays of colorful plumage or a song.

In the eastern US, one of the most reliable fireflies is Photinus pyralis, which is probably flying now pretty much everywhere. The males will hover over a field or lawn where females are hiding on the ground. Flying about belt-high or chest-high, they flash as they fly an upward swoop in the shape of the letter J. Then they stay near the top of the J and watch the ground for any female who replies. If the male thinks he has an interested female, he will descend to court her further. He will wait a few seconds, and if he doesn’t see a reply, then he will fly a few meters away and repeat the process. These fireflies are easily captured by children with jars, and there is no harm in encouraging your children to have a little fun with them.

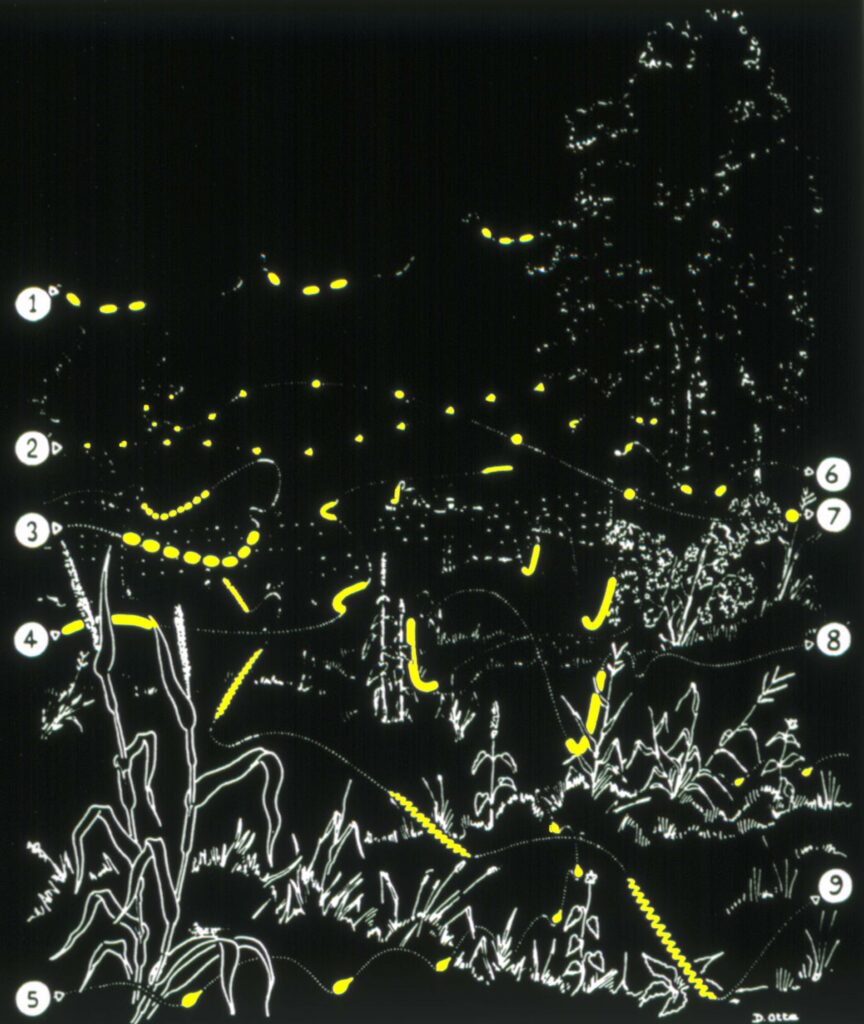

Watching fireflies as night falls, we can discriminate species by the different patterns of flashes. Whether the flash is long or short, in a string of multiples, if the male flies a pattern (as Photinus pyralis does), how high he is off the ground, if he is on the vegetation, the time of night that he flashes, all of these variables are used for females to recognize their males. On a good night in our area, a careful observer can distinguish four or more species by considering these elements.

But not all is beauty and love for flashing males, finding a receptive female can be very dangerous business. The genus Photuris includes species where the female will flash and if an eager male of a different species approaches she will kill and eat him. She also sequesters the toxins in his body so that now they protect her. This threat is very real; Many, sometimes most of the flashes we see among several species displaying at once are actually female Photuris, fishing for males, rather than males calling females, or honest females inviting courtship. It is sometimes claimed that the Photuris will mimic the call her intended victim expects, but there is no evidence for that, and it seems impossible that a female would know what the male of a different species expects in his duet.

One defense mechanism some males have against the Photuris is that they only respond to a female reply if it is very exactly timed following his display. Critical timing may require precision to the fraction of a second. If a female is expected to flash a reply 1.3 seconds after the male’s display, that male may not react to a flash that appears 1.8 seconds later. Too late, not his female. That would greatly reduce the likelihood of cheerfully rushing into an ambush just because he saw a flash of light.

The ability to control the flash permitted the evolution of one of the most interesting nocturnal phenomena, which is when many males perch in the same tree and then all flash or glow simultaneously such that the whole tree is synchronized. Visible from a good distance, the illuminated tree will attract females who then, presumably, compare males at close range to choose a mate.

Sit near nightfall on a warm summer night and watch Nature’s original fire works!