When children draw a tree, they often draw the lollipop style, a naked trunk with a ball of leaves on top. Or, they might draw the Christmas tree style, a triangle of green, perhaps with no visible trunk. While these are stereotypes that may work as analogy, real trees are unique, like snowflakes. Most species have a loose blueprint they are programmed to follow, and this can vary dramatically between species, as the lollipop does from the triangle.

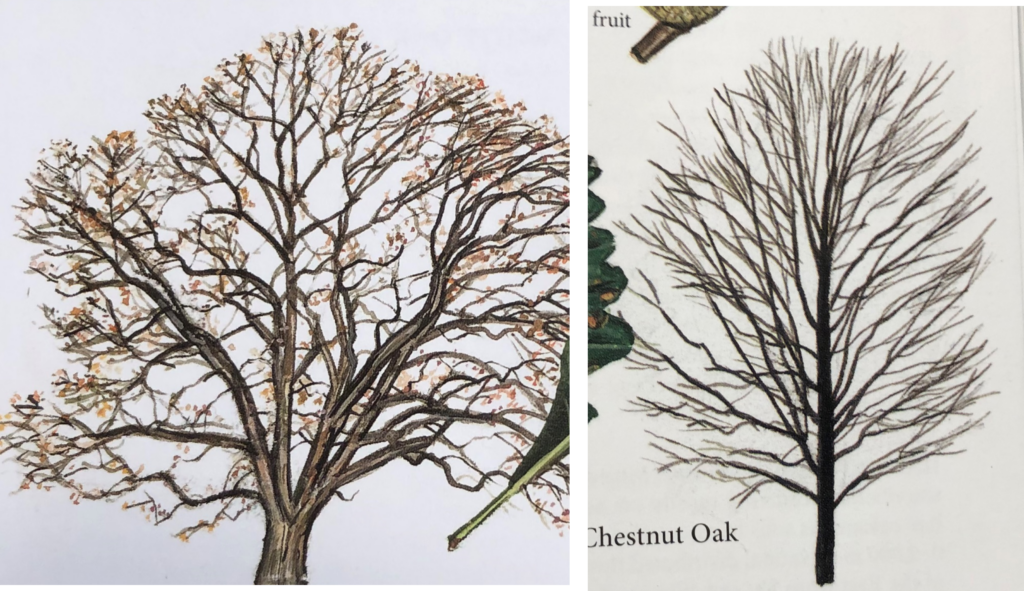

Most species have what botanists call a “habit” regarding their height and form. Field guides to trees try to provide an illustration of a typical individual, capturing any distinctive geometry of the species, so that the illustration will help identify a given tree. But, no tree will look exactly like the one in the book. This is very different from most animals that people are familiar with. The bones of animals are usually very closely this shape and arranged exactly just so. Yet, every tree is unique.

In addition to the general habit, every individual tree also has its own history of challenge and opportunity. In a season of ample water, perhaps the tree will bolt upward, straighter and taller than a neighbor of the same species who does not have good water. Without enough light, trees are blighted. With adequate-but-less-than-perfect light (perhaps overshadowed by an older tree) they grow bent toward the light. Some trees grow upward with a strong central leader, like the Christmas tree, others grow in all directions more evenly, as most hardwood trees do. Some grow fat and hemispherical in strong light with no neighbors.

When we say that trees grow, we are speaking about the branches. The trunk does not change other than getting wider: it does not expand the vertical space between branches. Side branches of some species appear in an orderly fashion, perhaps as a whorl around the trunk as in the majestic white pine. Other species do not follow a strict pattern. Some trees hold the branches on the older, lower regions of the trunk, being bushy below. Other species drop lower branches and develop straight smooth trunks with little sign of their earlier vestment.

Some species respond to their environment such that they can be tall and slender, or straight and wide, or very crooked. The Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) is such a tree, and I love to study the grand and crooked sycamores one commonly finds. Because they can be so many different architectures, I never know what to expect, and when I encounter a stand of sycamores, I pause a bit to look at them, and see how they differ, one to another. The big crooked one probably had no neighbors, and it is older than the other trees beside it today. Is the crooked one the mother of the straight ones? Did the crooked one get pruned back by an ice storm such that we see sharp bends in the trunk or branches today where stumps regenerated new growth? How long ago was that? The crooked tree is telling you a rich life history, if you take the time to look.

There is an undeniable majesty to the straight and towering redwood, its stubborn persistence with a single plan throughout the centuries. But, I prefer crooked trees. The crooked tree shows every insult it has survived, every opportunity it exploited. A crooked tree tells a story upon first sight. The crooked tree shows a different kind of persistence from the redwood, one more akin to “if I can’t make this work, okay, I’ll go the other way.” I like that personal story.