Every child learns in school that we have five senses, and students are trained to identify vision, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Yet, this universal lesson is far from true. Chemical sensation is basically the same thing in smell and taste, which would take us down to four. As an experiment, hold your nose shut as you eat, and you will discover your sense of taste suffers. But the real error is that we sense a great deal more than just these modalities. We certainly sense that the campfire is radiating heat to our face, whereas our back is cold. If we swim underwater, our ears feel greater pressure when we dive deeper. Also, our ears tell us we are upside down or right-side up. Sensing how we are oriented is why we can ride a bicycle, and it becomes almost subconscious with practice. We sense acceleration, as when our car goes around a corner. Most people sense the passage of time as demonstrated by them waking up at about the same time every day, or becoming hungry at meal time, no matter what their nutritional state is. There are more than five senses, although we are not fully conscious of them all.

Other animals make great use of stimuli we don’t sense well. Pit vipers detect heat so precisely that they probably have infra red images of their prey at night. Ants, bees, and wasps can see polarized light, detecting the angles of the light waves in the sky above, which we do not see at all, and they use this to navigate with great precision. Sharks, electric eels, and knife fishes can detect the electric fields of living animals and may use this sense to find prey. A knife fish can actually use its own electric field to navigate around objects in cloudy water, and can even go through a maze backwards because it doesn’t require vision.

Many animals detect the magnetic field of the Earth and use it for long distance navigation, or simply to get back home. We do not have any way to detect carbon dioxide, but mosquitos and ticks use it to find us quickly for their blood meal. Although we do sense time, we are not close to the level of the honey bee. Bees can tell the difference between 2.1 seconds and 2.2 seconds. At the other end, they can be trained to come to a particular place in intervals of 13 hours. What is most remarkable is it appears they may assess their performance of certain foraging duties by using an inverse of the time it took to achieve the goal. The reward is devalued if it takes longer to obtain, so if it took two minutes to accomplish the job, then multiply by ½, if it took ten minutes multiply by 1/10, if it took forty minutes multiply by 1/40, and this ranking provides the relative value of the job. While I think I can get the “feel” of two minutes, or ten, or forty, exactly how to relate that to the inverse of time seems to be beyond my imagination. And this brings up the distinction between reception (detecting something) and perception (making sense of the information).

Reception and perception are different things, and sometimes our senses (reception) deliver information that our brains (perception) ignore. Called “habituation,” the learned elimination of a stimulus from our conscious decision-making is a major aspect of intelligent behavior: Pay attention to important things, ignore inconsequential things. Consider that if you enter an office space to conduct business you will likely not pay any attention to the background noise of the air conditioning. But you are not deaf to it, you are just throwing that information away, as can easily be seen if the air conditioning suddenly goes off. You will say “hey, the air conditioner just went off.” So, your initial lack of awareness of the air conditioning was an aspect of perception, not sensory reception. More dramatically, a mother in a big city will sleep through an emergency siren in the street, but wake up right away if her baby cries in the other room.

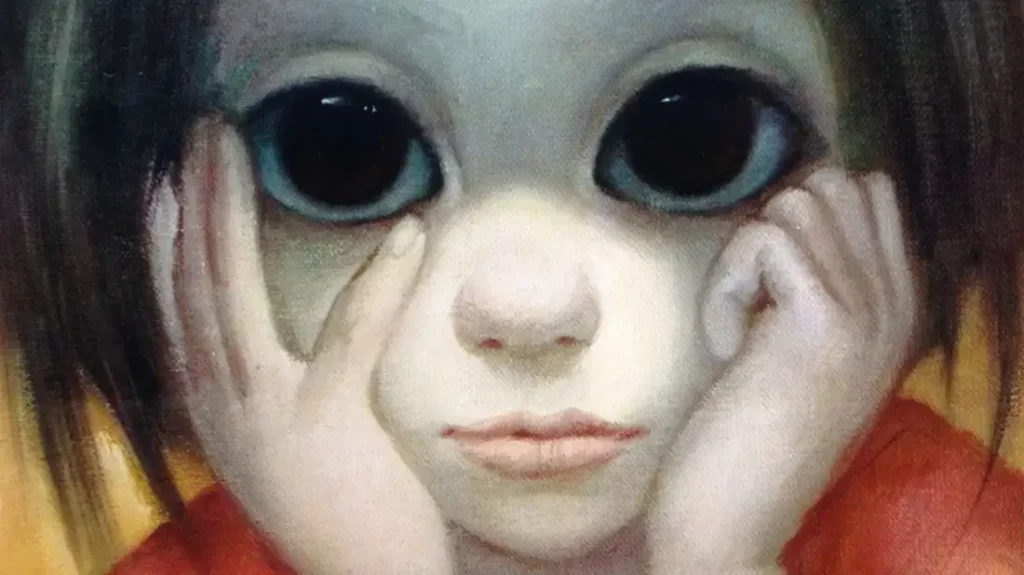

People commonly claim to have sensed something that they only perceived. Consider the claim “I could feel his cold stare upon me.” We cannot feel a person stare because his eyes create no force for us to detect. However, if we see the expression on his face, we may interpret his hostile intent, and we are conscious of this perception. Of course, there are elements of reception and perception that are unconscious to us. We may be largely unaware that we sensed something that caused us to have certain thoughts or feelings. One example is that the pupils of our eyes dilate when we are affectionate or facing someone we are attracted to. Without being conscious of it, we may receive this signal from another person, and decide that we like that person too. The correct perception of mutual affection was launched by the subconscious. This trick of making the eyes look bigger to inspire affection is widely used in both the cosmetic industry and in sentimental or kitsch artwork. Aww, such cute little kids!