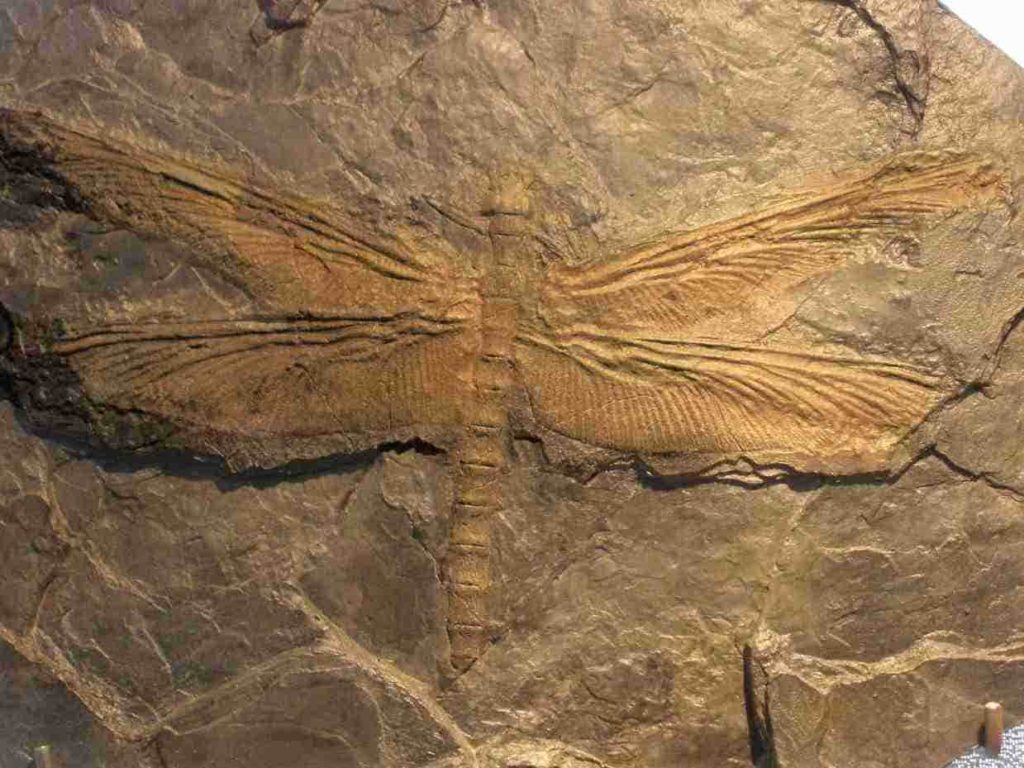

Everyone knows dragonflies and their close relatives (scientifically named Odonata), and I admire them for their agility, vigilance, and skilled flight. They are among the oldest lineages of terristrial animals still alive, dating back to 300 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs. Before the evolution of flying reptiles and birds, the odonates were the dominant flying predators on the planet. They were larger then than they are now, with the largest estimate of their size at a foot and a half long and a wingspan of more than two feet (officially, 47cm long and 75 cm across). I have seen a fossil wing that is more than 10 inches long, and so if you count that twice (left and right) and add a few inches for the thorax and its muscles, you can get to about two feet across based on that one fossil.

Odonates come in two flavors today, the larger and more powerful dragonflies, and the more slender and graceful damselflies. Odonates hold the crown for “best fliers,” forward, backward, and including the ability to hover in a small updraft without beating the wings at all. They use their great vision to remain in the same place, and they tilt their wings, balancing lift and drag in the air column, to stay still. They fly with four wings, as do most insects, but unlike all others, they can move the front and back pairs independently. As the front wing goes up, the back goes down. (In all other insects the wings move together, left and right, front and back.) This allows for great precision in flight path and velocity. Of course, a good pilot needs good vision, and odonates have among the most holographic eyes in the insect world, offering close to a complete sphere of perception.

Odonates are aquatic as immatures, predators hunting other invertebrates or tadpoles and small fish. Both dragonflies and damselflies can strike by expressing their mandibles out on a strong appendage, an explosive attack that will capture any prey within a centimeter or so of the otherwise stationary hunter.

Adult dragonflies are usually seen hunting over water or fields where their insect prey is in flight. Damselflies favor water, too, but they will range deep in the forest, often looking for spider webs where they may steal prey from the web or even take the spider.

We do not understand the migratory life of dragonflies, but evidently some species leave their north temperate range and fly south for the winter. There are no known hibernation sites like those of the monarch butterflies, but in summer the dragonflies are back. Modern technology allows us to track individual dragonflies with small radio tags, and perhaps soon we will know where they go in winter. A recent study from Rutgers University using genetic survey data, published in the journal PLoS, indicates that the small dragonfly, Pantala flavescens, covers the globe like no other animal. Some of these insects are flying such great distances as a regular habit that insects collected in Texas, eastern Canada, Japan, Korea, India, and South America are essentially all one population.

One of the particularly interesting features of dragonflies and damselflies is that their mating habits rely completely on female choice. Male coercion (forcing copulation) is impossible. This is because the male grasps a potential mate behind her head with a set of claspers that is at the end of his abdomen. However, his genitalia are much further in front, and so the female must bend herself forward to unite the end of her abdomen with the middle of his body. This is called the ”wheel” position, and it is impossible for the male to fertilize a female without her compliance. Further, males have a small scooper they can use to remove the sperm of a male who already inseminated the female. If she is unhappy with her earlier choice in males, she only has to couple with another male, and he will eliminate the first suitor’s sperm. It is hard to find other animal species where the female is in such complete control of her reproduction.